Reviews - Wonderful Town

Wonderful Town

Reviewed By John Stakes

Wonderful Town

Download the original attachment

KESWICK FILM CLUB

“Wonderful Town”

To understand and appreciate Thai director Aditya Assarat’s debut feature film “Wonderful Town” screened last Sunday, it is helpful if not essential to know what lay behind the making of the film.

In 2004 coastal parts of Thailand were devastated by a tsunami following an undersea earthquake. The town of Takua Pau was particularly badly hit losing over 8000 of its residents. Two years later Assarat returned to this once wonderful town to find that it had been largely rebuilt and showing few signs of the terrible devastation.

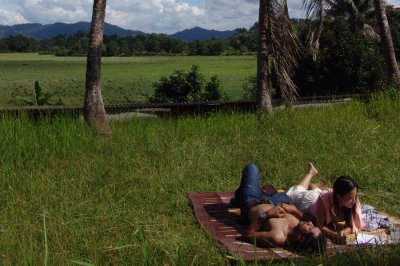

However Assarat was struck by the sadness which still pervaded everyone’s lives and lent an eerily strange feel to their surroundings. It was as if the town were still in a state of shock although the outward signs were of almost complete recovery. He decided to try to capture the essence of his feelings by focusing his film on a modest family hotel situated on the coastal strip between the mountains and the shore and run by the young, hauntingly attractive but withdrawn Na and her brother Wit.

The hotel had clearly enjoyed better days, but, as Na explained to her new guest, a junior architect Ton from Bangkok, most of the tourists had come to prefer the facilities of the recently developed coastal strip before the giant wave struck. Not quite as run down as a certain Bates Motel perhaps but no other guest was seen arriving or leaving during Ton’s stay. So there was an eerie silence about the place and little also broke the silences between Na and Ton as they edged towards their inevitable coupling.

The backgrounds of both were left largely unspoken of let alone explored. Na was looking after Wit’s child but the whereabouts of the child’s mother remained a mystery (had she been killed in the tsunami?). Ton presented himself as a loner with a preference for countryside over city life or so he said, but in one telling but still confusing phone call from his car towards the end of the film it appeared he had resolved, having nevertheless just consummated his tentative relationship with Na, to return to a former girlfriend who was prepared to have him back.

Wit turned out to be a nasty, lazy, resentful individual, overprotective of his sister for entirely selfish reasons. A self confessed gangster, he is the perpetrator of the one act of physical violence in the film when Ton is set upon and beaten to death, his corpse being floated down river to the sea. Although there had been some minor intimidation of Ton earlier nothing had prepared us for his sudden death which came as a considerable shock. Assarat’s camera had spent much of the time up to this point as a discreet observer of the banality of Na’s life and capturing the boredom of Ton’s assignment in monitoring progress on a reconstruction site.

Perhaps the sparse dialogue of Assarat’s own screenplay was intended to reflect the inability of the population to adjust to their enormity of their collective loss. But as we rarely strayed into the wider community, its use seemed merely to echo the gulf of experience between the city man and rustic girl, or maybe to reflect the apparent natural reticence of each. We were expected to fill some large narrative gaps ourselves for no particular reason and the closing scene involving two child dancers initially totally baffled this reviewer

However, perhaps in the deliberately slow build up of their relationship, and in Ton’s failure to see the resentment building around him, followed by the sudden violent denouement Assarat was creating a personal tsunami for the doomed couple. And the healing of the community’s wounds would only be achieved through the innocence of children.

This was Assarat’s first foray into full length feature filming from a background of shorts and documentaries and his inexperience showed. However he handled the development of the doomed couple’s initially tentative relationship well and the seeds of a potentially haunting film were at least sown if not harvested. His film has enjoyed success beyond his own country’s borders and won the Tiger award at the 2007 Rotterdam Film Festival. And like Thailand’s emerging fragile economy Assarat may yet provide his many sponsors and backers with a return on their investment.

KESWICK FILM CLUB

“Wonderful Town”

To understand and appreciate Thai director Aditya Assarat’s debut feature film “Wonderful Town” screened last Sunday, it is helpful if not essential to know what lay behind the making of the film.

In 2004 coastal parts of Thailand were devastated by a tsunami following an undersea earthquake. The town of Takua Pau was particularly badly hit losing over 8000 of its residents. Two years later Assarat returned to this once wonderful town to find that it had been largely rebuilt and showing few signs of the terrible devastation.

However Assarat was struck by the sadness which still pervaded everyone’s lives and lent an eerily strange feel to their surroundings. It was as if the town were still in a state of shock although the outward signs were of almost complete recovery. He decided to try to capture the essence of his feelings by focusing his film on a modest family hotel situated on the coastal strip between the mountains and the shore and run by the young, hauntingly attractive but withdrawn Na and her brother Wit.

The hotel had clearly enjoyed better days, but, as Na explained to her new guest, a junior architect Ton from Bangkok, most of the tourists had come to prefer the facilities of the recently developed coastal strip before the giant wave struck. Not quite as run down as a certain Bates Motel perhaps but no other guest was seen arriving or leaving during Ton’s stay. So there was an eerie silence about the place and little also broke the silences between Na and Ton as they edged towards their inevitable coupling.

The backgrounds of both were left largely unspoken of let alone explored. Na was looking after Wit’s child but the whereabouts of the child’s mother remained a mystery (had she been killed in the tsunami?). Ton presented himself as a loner with a preference for countryside over city life or so he said, but in one telling but still confusing phone call from his car towards the end of the film it appeared he had resolved, having nevertheless just consummated his tentative relationship with Na, to return to a former girlfriend who was prepared to have him back.

Wit turned out to be a nasty, lazy, resentful individual, overprotective of his sister for entirely selfish reasons. A self confessed gangster, he is the perpetrator of the one act of physical violence in the film when Ton is set upon and beaten to death, his corpse being floated down river to the sea. Although there had been some minor intimidation of Ton earlier nothing had prepared us for his sudden death which came as a considerable shock. Assarat’s camera had spent much of the time up to this point as a discreet observer of the banality of Na’s life and capturing the boredom of Ton’s assignment in monitoring progress on a reconstruction site.

Perhaps the sparse dialogue of Assarat’s own screenplay was intended to reflect the inability of the population to adjust to their enormity of their collective loss. But as we rarely strayed into the wider community, its use seemed merely to echo the gulf of experience between the city man and rustic girl, or maybe to reflect the apparent natural reticence of each. We were expected to fill some large narrative gaps ourselves for no particular reason and the closing scene involving two child dancers initially totally baffled this reviewer

However, perhaps in the deliberately slow build up of their relationship, and in Ton’s failure to see the resentment building around him, followed by the sudden violent denouement Assarat was creating a personal tsunami for the doomed couple. And the healing of the community’s wounds would only be achieved through the innocence of children.

This was Assarat’s first foray into full length feature filming from a background of shorts and documentaries and his inexperience showed. However he handled the development of the doomed couple’s initially tentative relationship well and the seeds of a potentially haunting film were at least sown if not harvested. His film has enjoyed success beyond his own country’s borders and won the Tiger award at the 2007 Rotterdam Film Festival. And like Thailand’s emerging fragile economy Assarat may yet provide his many sponsors and backers with a return on their investment.

Find A Film

Search over 1500 films in the Keswick Film Club archive.

Friends

KFC is friends with Caldbeck Area Film Society and Brampton Film Club and members share benefits across all organisations

Awards

Keswick Film Club won the Best New Film Society at the British Federation Of Film Societies awards in 2000.

Since then, the club has won Film Society Of The Year and awards for Best Programme four times and Best Website twice.

We have also received numerous Distinctions and Commendations in categories including marketing, programming and website.

Talking Pictures

The KFC Newsletter

Talking Pictures

The KFC Newsletter

Links Explore the internet with Keswick Film Club