Reviews - The Turin Horse

The Turin Horse

Reviewed By John Porter

The Turin Horse

Over a black screen a Hungarian voice tells us that after seeing a work-horse whipped in the street, Friedrich Nietzsche threw his arms around the animal’s neck before collapsing into hysteria and madness. In this state and wordless, he lived the rest of his days. Next we see a horse pulling a cart. For five minutes or more the Alhambra's Sunday audience watched this, without the interruption of a cut, as the first shot in Bela Tarr's much heralded final movie, 'The Turin Horse'. For the next two and a half hours, Tarr's vision unfolds and refolds, again and again as some desolate fable of the downtrodden. This is a fable not of living, but of existing, and of the unexplainable demise that takes grip without warning to push towards an end.

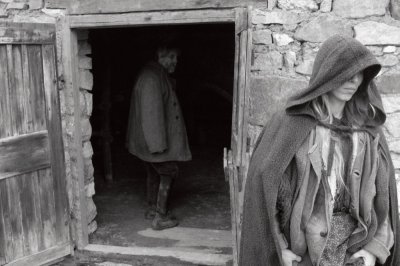

A father and daughter live upon the wastes of an unspecified land, where each day brings the same routine of dressing, working, eating boiled potatoes, and sleeping. The wind is relentless. Dust obscures what lies beyond, and life is blank. Apart from one long passage of dialogue from a neighbour who comes to the house to borrow brandy, speech is sparse and loveless. Into this world is placed our sad, simple tale, divided up into days, which are each marked by an inter-title.

Some viewers have found the film difficult because of the repetition, and because in contrast to the usual paradigms of cinematic narrative, the very little that happens here, happens slowly. Yet only through this method can Tarr show gradual changes of circumstance, and their reflections on the protagonists' world, so building up an all-pervading, and very specific atmosphere of hopelessness. First the horse won't work: so the people don't work. Then the horse won't eat, and the people become less interested in their meals. Next, the horse won't drink. Under layers of shawls and hair, whipped around by the wind, the daughter goes to collect water one morning to find the well dry. At first the long takes forced us to observe. By this point however, they are forcing us to share in the gaunt dread that something unforgiving, and utterly unstoppable, is in its final throes.

The director uses these long, beautifully choreographed shots to arrive subtly upon his exquisite compositions, not using cuts to make the visual balances in them more obvious. For the viewer, this is a world of discovered pleasures, and seemingly accidental, hidden beauty. In this way Tarr's three or four minute shots without an edit not only stretch the concept of time, but also serve to fall upon the natural rhythms of movement, and show the poetry of the everyday.

At only two points is the past referenced, once when the father mentions that the woodworms have stopped burrowing after years in the rafters, and secondly when we see the daughter carefully handle a photograph, presumably of her mother. Leaving aside any elemental or universal undercurrents, physically, this is a story that takes place in the Now; What we learn about the characters comes from tiny nuances of poise and movement during their relationship to the world around them. In giving the fleeting view of a history within the photograph, a shocking realisation is also brought to the fore: In the conventional sense, we know literally nothing about these people. Yet we know everything necessary, and we are watching them slowly disintegrate under layer upon layer of inexplicable strifes.

The obvious parallels to the works of Andrei Tarkovsky have been noted elsewhere, but we can also see a continuation of visual style from even earlier by looking at the similarities in Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1955 work, 'Ordet'. The minimalist construction of the sets in both movies provide an antithesis to the rural ideal of blue sky and green trees, and in Tarr’s case, the rough textures are presented to the viewer as the reality of life when it is placed in the context of hardship and filtered through his black and white lens. If the visual style of the movie is one of minimalism, then the sound design too is created as such. Pieces of noise, disembodied from the characters’ actions, stab onto a background canvas of aural monotony provided either by the wind, or Mihaly Vig’s trudging score.

A final religious slant is lent to the picture when the daughter reads passages from a zealotic leather-bound book, which through her broken tongue, prophecies doom and the destruction of the world. It seems that this must happen. There is no deviating from the path, yet no reasons are given as to why, either within the volume’s pages or during the movie itself. Ultimately we are left with more questions than answers. Perhaps there are no answers. Perhaps it is enough in these days of the mainstream cinematic apocalypse to enjoy an unusual style in the hands of an artist coming to terms with saying goodbye to his art.

This Sunday brings Keswick Iciar Bollain’s ‘Even the Rain’, and its musings on history, cinema, and exploitation in South America.

A father and daughter live upon the wastes of an unspecified land, where each day brings the same routine of dressing, working, eating boiled potatoes, and sleeping. The wind is relentless. Dust obscures what lies beyond, and life is blank. Apart from one long passage of dialogue from a neighbour who comes to the house to borrow brandy, speech is sparse and loveless. Into this world is placed our sad, simple tale, divided up into days, which are each marked by an inter-title.

Some viewers have found the film difficult because of the repetition, and because in contrast to the usual paradigms of cinematic narrative, the very little that happens here, happens slowly. Yet only through this method can Tarr show gradual changes of circumstance, and their reflections on the protagonists' world, so building up an all-pervading, and very specific atmosphere of hopelessness. First the horse won't work: so the people don't work. Then the horse won't eat, and the people become less interested in their meals. Next, the horse won't drink. Under layers of shawls and hair, whipped around by the wind, the daughter goes to collect water one morning to find the well dry. At first the long takes forced us to observe. By this point however, they are forcing us to share in the gaunt dread that something unforgiving, and utterly unstoppable, is in its final throes.

The director uses these long, beautifully choreographed shots to arrive subtly upon his exquisite compositions, not using cuts to make the visual balances in them more obvious. For the viewer, this is a world of discovered pleasures, and seemingly accidental, hidden beauty. In this way Tarr's three or four minute shots without an edit not only stretch the concept of time, but also serve to fall upon the natural rhythms of movement, and show the poetry of the everyday.

At only two points is the past referenced, once when the father mentions that the woodworms have stopped burrowing after years in the rafters, and secondly when we see the daughter carefully handle a photograph, presumably of her mother. Leaving aside any elemental or universal undercurrents, physically, this is a story that takes place in the Now; What we learn about the characters comes from tiny nuances of poise and movement during their relationship to the world around them. In giving the fleeting view of a history within the photograph, a shocking realisation is also brought to the fore: In the conventional sense, we know literally nothing about these people. Yet we know everything necessary, and we are watching them slowly disintegrate under layer upon layer of inexplicable strifes.

The obvious parallels to the works of Andrei Tarkovsky have been noted elsewhere, but we can also see a continuation of visual style from even earlier by looking at the similarities in Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1955 work, 'Ordet'. The minimalist construction of the sets in both movies provide an antithesis to the rural ideal of blue sky and green trees, and in Tarr’s case, the rough textures are presented to the viewer as the reality of life when it is placed in the context of hardship and filtered through his black and white lens. If the visual style of the movie is one of minimalism, then the sound design too is created as such. Pieces of noise, disembodied from the characters’ actions, stab onto a background canvas of aural monotony provided either by the wind, or Mihaly Vig’s trudging score.

A final religious slant is lent to the picture when the daughter reads passages from a zealotic leather-bound book, which through her broken tongue, prophecies doom and the destruction of the world. It seems that this must happen. There is no deviating from the path, yet no reasons are given as to why, either within the volume’s pages or during the movie itself. Ultimately we are left with more questions than answers. Perhaps there are no answers. Perhaps it is enough in these days of the mainstream cinematic apocalypse to enjoy an unusual style in the hands of an artist coming to terms with saying goodbye to his art.

This Sunday brings Keswick Iciar Bollain’s ‘Even the Rain’, and its musings on history, cinema, and exploitation in South America.

Find A Film

Search over 1475 films in the Keswick Film Club archive.

Friends

KFC is friends with Caldbeck Area Film Society and Brampton Film Club and members share benefits across all organisations

Awards

Keswick Film Club won the Best New Film Society at the British Federation Of Film Societies awards in 2000.

Since then, the club has won Film Society Of The Year and awards for Best Programme four times and Best Website twice.

We have also received numerous Distinctions and Commendations in categories including marketing, programming and website.

Talking Pictures

The KFC Newsletter

Talking Pictures

The KFC Newsletter

Links Explore the internet with Keswick Film Club